‘Wisdom’ of Guatemala’s indigenous people needed for sustainable development: a UN Resident Coordinator blog

“Now more than ever, we must heed the wisdom of indigenous peoples. This wisdom calls upon us to care for the earth so that not only our generation may enjoy it, but that future generations may as well.”

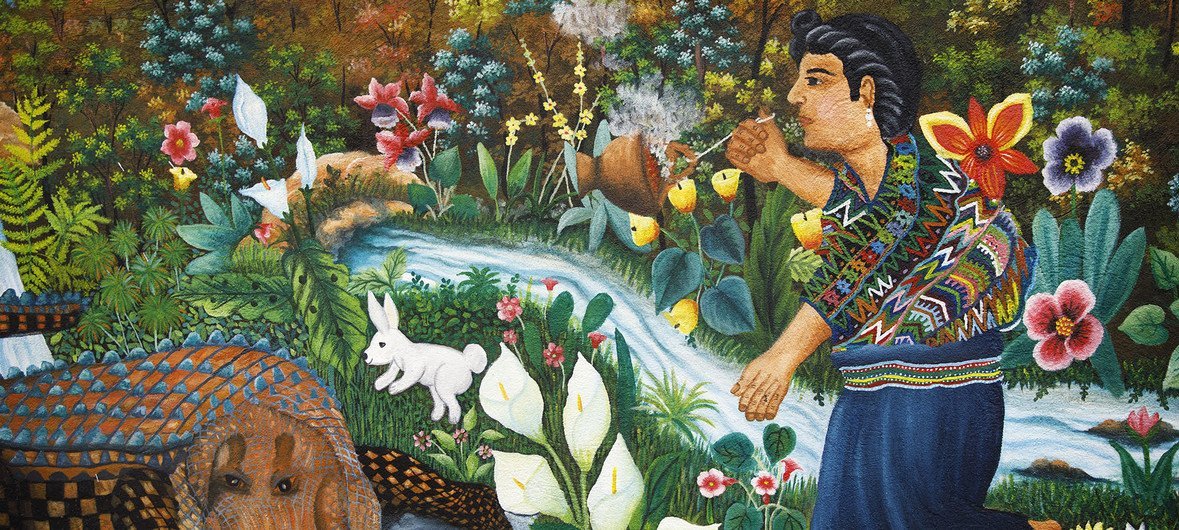

This wisdom is passed down to us through stories and spirits. Consider the example of Nawal, a supernatural spirit of harvests that can take on animal forms, according to Mesoamerican beliefs. On certain days in the indigenous calendar, people call on Nawal for a good harvest. It is a fine thing to have one good harvest. It is even better for the earth to yield its bounty again and again. To enjoy such repeated success, farmers in the area know they must respect the seasons, to plant, to sow, to let the land lay fallow for a time.

This wisdom was also articulated in a declaration from 2012, on an auspicious date in the Mayan calendar. It was Oxlajuj B’aktun or a “change of era,” the end of a cycle that lasts more than 5,000 years. On that date, the three UN entities working with indigenous peoples came together in Guatemala, their first joint meeting outside the UN’s New York headquarters.

Together, they issued a declaration pleading with humanity to respect human rights, promote harmony with nature, and pursue development that respects ancestral wisdom. These three bodies included the Permanent Forum for Indigenous Issues, the Mechanism of Experts on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

This wisdom found its way into “K’atun: Our Guatemala 2032”, the national plan which has guided sustainable development of three successive administrations. It serves as the compass for the country’s UN Cooperation Framework for Sustainable Development 2020-2024, created in collaboration with the Government of Guatemala.

Indigenous Guatemalans hit hardest by coronavirus pandemic

To pursue K’atun, we must look at the status of indigenous peoples. In Guatemala, they are amongst the most vulnerable people because they are constantly displaced from their ancestral lands. Data from recent years show that the poverty rate among indigenous people was 79 per cent, almost 30 points above the national average. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic eight out of every 10 indigenous girls, boys and adolescents, live in poverty. Only six finish primary school, only two go to secondary school, and one goes to university. Six in 10 indigenous children under five years of age suffer from chronic malnutrition.

COVID-19 is devastating for all of Guatemala. Many people are sick, some are dying, and countless others are losing their livelihoods because of the disease itself and because the quarantine prevents them from working and earning money.

However hard the pandemic hits Guatemala, it will hit the indigenous peoples even harder. They were already the furthest left behind, and now they will be set back even more. The situation of indigenous women, who are often the main providers for their families, is even more worrisome.

Indigenous people hold key to collective survival

And yet, indigenous people are seeking their own solutions, drawing on their own ingenuity. They are using traditional knowledge and practices to contain the disease.

We all must concern ourselves with the wellbeing of indigenous peoples, for their sake. We must respect their wisdom, for their sake. We must protect their human rights, for their sake. We must include them in decision-making, for their sake. It is only right.

But we must also do this for the sake of all Guatemalans. All of Guatemala, indeed, the whole world, has much to learn from indigenous peoples. It is a painful irony that they have been so exploited and oppressed, and yet they may hold a key to our collective survival. It is a painful irony, too, that indigenous people are among those most affected by climate change, and yet they contribute the least to it.

Without indigenous people, neither Guatemala nor the rest of the world will achieve sustainable development. Without indigenous people we cannot enjoy the gifts of the earth and maintain them for all those who will come after us. This is and must be the work of all governments and all people.

75 years ago, the signatories of the United Nations Charter reaffirmed “the dignity and worth of the human person.”

Now, let us reaffirm that belief once more. And let us ensure that indigenous people are included in it.”