OPINIONISTA: An essay: SA’s economic decline in detail – and the narrow path away from failure

My company, Eunomix, advises governments and corporations on reducing fragility, decreasing risk and improving resilience. We guide development policy and investment strategies, and integrate geopolitical and country risk into corporate strategy, enterprise risk and operations management. Our offering responds to the challenges of an increasingly complex global society through a big-data state-centric model. This detailed analysis examines the developmental state in South Africa, the causes of state performance decline, and outlines a narrow path away from failure

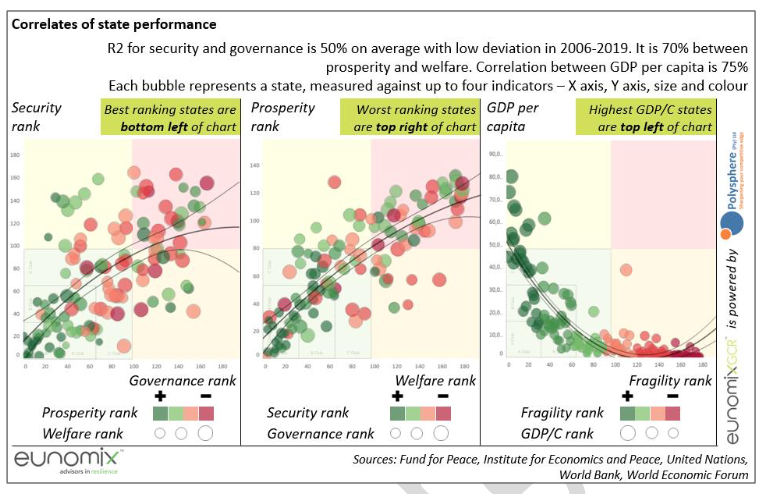

Eunomix measures state performance through four public goods which represent the capacity to deliver and the outcome – delivery itself. Security accounts for the protection of the state from internal and external violence and conflict. Governance accounts for the form and performance of the state’s political system. Prosperity accounts for the economic system and its performance. Welfare accounts for human capital and the environment. State fragility is an overall indicator of capacity and performance.

We have our own indicators. However, for this analysis we have used established third-party indicators: for security, the Global Peace Index; for governance, the World Governance Indicators and the Democracy Index; for prosperity, GDP per capita and the World Competitiveness Index; for welfare, the Human Development Index; and, for fragility, the Fragile State Index. We have extensively analysed and processed them to provide uniform ranking and scoring. All data other data is sourced from the World Bank, unless stated otherwise.

Our measuring of state performance is agnostic to its means: conservative or progressive, centralist or federalist, technocratic or devolved, collectivist or capitalistic, democratic or not. We only account for capacity and outcome.

Our model shows a persistently strong correlation between security, governance, prosperity and welfare. And all correlate with fragility. The vast majority of countries cluster along strong to weak state performance axis. Outliers are, by definition, exceptions. As such they provide essential evidence for statistical observation and generalisation within our model.

Best performing states provide security, good governance, higher prosperity and social welfare. Worst performing states fail on all these measures. In-between is distributed the majority of states, with varying levels of performance along the spectrum of the public good.

Objective and structure of the essay

This essay is an application of the model to South Africa at a time of pronounced and accelerating decline. We seek here to contribute a rigorous understanding of the country’s performance, derive a fresh assessment of its causes, identify key obstacles to durable development, and outline a pragmatic solution toward a more sustainable future.

On the Coronavirus pandemic itself, the essay presumes that it will continue to expand until either herd immunity has been reached or a vaccine has been found and rolled out, neither being likely to occur in the next six months.

The essay’s the first section presents our model-derived key insights and findings on durable development and the developmental state. We do so by presenting these findings through an iterative narrative of ‘discovery’ through statistically significant didactic ‘clues’. The second section compares South Africa’s performance against peer countries over a decade or so, then diagnoses that performance against our key insights and findings. The essay concludes with the outline of what an achievable strategy toward durable development in South Africa could entail, and the conditions for its adoption.

Section 1: Durable development and its requirements

Clues

Clue 1: democracy

Good governance is a mark of durable development. But only very small numbers of countries have durably developed (the ‘late-developers’ of the 1980s-1990s) without having also durably democratised. All but one, China, are oil-rich. A handful of non-oil countries have tried and failed to durably develop without democratising – Morocco, Jordan, Tunisia. A few recently embarked on that path – Cambodia, Ethiopia, Myanmar, Lao, Rwanda. Only Vietnam has so trekked China’s path.

Bar China, all non-oil late-developers durably democratised – Hong Kong, Malaysia, Taiwan, Singapore, South Korea; most of Central Europe. Some non-oil countries started transitioning in both development and democracy but are experiencing reversals – Thailand and Turkey.

In the group of about twenty-five oil-rich countries, only five have been durably democratic. Of these, only three have been developed. Of the twenty non-democratic only six have been durably developing – all in the Middle East. Two others have been somewhat developing – Azerbaijan and Russia. The remaining thirteen are neither developing nor democratic. They are highly fragile or failed – Iraq, Libya, Venezuela.

The prospects of mineral-rich countries are worse. Of the twenty-five, only two are developed – Australia and Chile. Three are middle-income – including South Africa. The rest (80%) are lower-income, highly fragile or failed. Half the mineral-rich countries are on the democracy spectrum. But the transition to democracy has not correlated with development nor lower fragility. No mineral-rich country is or has been developing while being non-democratic.

There are only about seven developed-non-democratic countries – six of which oil-rich – and about thirty non-developed-democratic countries; barely 20% of the total.

A further six are experimenting with development without democratisation – only Vietnam having made meaningful progress. The majority, 80% belong are either developed-democratic, neither or somewhere in-between. In this group, non-oil late-developers which started out non-democratic democratised along the way and have remained so.

Clue 2: natural resources

Oil production is capital-intensive and yields enormous wealth. Developed Middle East producers generate high returns even with low oil prices because their industry has long been amortised. Resource rents in these countries averaged 30% of GDP. Economic growth was 5.5% per annum in 2000-17, and 7% per annum during the commodity super-cycle of 2004-14. Their elites maintain political control through wide patronage and targeted repression. Vast fiscal resources finance generous welfare states, fiscal stabilisation instruments and expensive diversification strategies for their post-oil future.

Non-developed oil-rich countries maintain control through targeted patronage and wide repression. Their elites do not invest in social welfare, economic stabilisation and post-oil despite rents also averaging 30% of GDP. Their growth was 5% in 2000-17 and highly volatile. They are often conflict-affected, and risk grave political and socio-economic predicament once the resource has been exhausted. They are prisoners of the resource-curse. Conflicted-affected countries’ resource rents have averaged 20% of GDP per annum.

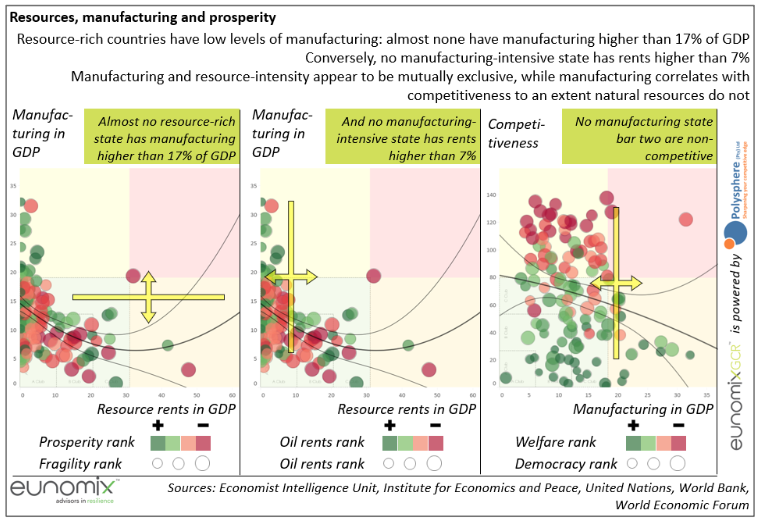

Minerals return rents half as high as oil, averaging 14% of GDP. Mineral rich countries grew on average 4.5% per annum in 2000-17, with very low volatility. These rents are insufficient to fund durable development, though generally enough for their elites to maintain power through targeted patronage and wide repression. They cannot concurrently fund welfare states, stabilisation funds and diversification strategies. They are often conflict-affected. They are prisoners of a deeper resource-curse.

Durable development

Wealth and the people

Oil-rich countries do not need their people to generate wealth, which is produced in capital-intensive enclaves. Elites in most of these countries are predatory, to devastating effects on development, condemning their populations to the struggle for survival. Mineral-rich countries do not generate enough wealth, without also mobilising their population. Few do so.

Non-oil late-developers all deployed labour-intensive-export-oriented growth strategies, which depend on the mass mobilisation of their population. Elites, facing mass unemployment, and absent the option of confiscating natural resources for power, selected this strategy out of necessity.

Except for rare exceptions – Costa Rica, Mauritius – most non-oil late-developers started their labour-intensive-export-oriented strategies as non-democracies. But as their social capital upgraded and transitioned from poverty to middle-class they democratised. Development and democratisation cooperated to upgrade human and social-capital, allowing transition from labour to technology-intensive, and ensuring durable development.

In recent decades about thirty low-income countries democratised across Africa, Asia and Latin America. Precious few have been developing – Indonesia, the Philippines. A few have experienced recent reversals. These countries share a crucial attribute: they all have low levels of human development.

Absent oil, durable development depends entirely on human capital. Economic development (gains in prosperity) almost perfectly correlates with human development (gains in welfare) for a staggering 90% of countries in the past two decades. Human development is the most reliable predictor of durable prosperity and strong state performance.

Non-oil countries thus have extremely limited options. They either initiate development through the mobilisation of their labour or condemn themselves to stagnation. But adoption of labour-intensive-export-orientation not accompanied by human and social-capital upgrading is insufficient for durable development. Many countries have found themselves in a ‘race to the bottom’. Labour-intensive industries contribute vital employment and some political stability, but fail on their own to lead to higher-income / low-fragility: Bangladesh, Honduras, Madagascar.

Financial capital and markets

Neither oil-rich, mineral-rich nor labour-rich low-income countries possess sufficient endogenous financial and social-capital and large enough markets to fund initial development. They must rely and external sources of investment for fixed capital, and on external markets to absorb production. The development process progressively lowers dependency toward external financial and social-capital. But it lowers dependency on external markets much less. Instead, late-developers increase the depth, scope and direction of economic interaction with their economic partners.

The developmental state

The politics of development

Development often represents a risk to elites – the groups who control or dominate the state. Those who adopt it do so in response to a serious threat to their interests that cannot be addressed otherwise – economic collapse, revolution, dangerous neighbour. Those who resist it either can afford to or underestimate the threat. Zimbabwe is a poster child for this condition; Mali one where an elite is disincentivized from initiating development by external military intervention.

The transition from labour to capital-intensive development is fraught. Low investment in human capital and infrastructure might thwart it. Transition to capital-intensive industries might be too costly, too exclusive or too early in the process. Elites may successfully resist democratisation. Any of these challenges may result in aborted development. Brazil, Egypt, Jordan, Thailand, Tunisia and Turkey are examples of this.

China’s experiment of development without democracy has yet to succeed. Its economic development still outstrips its human development. Only one-third of the population has entered its vast middle-class. That expansion is the greatest threat to an elite increasingly fearful of dissent and democracy within ‘Greater China’ – Hong Kong, Tibet, Taiwan, Xinjiang. Internal suppression, fiscal profligacy and aggressive foreign policy represent the elite’s attempt at managing this irrepressible threat.

The developmental state (re)defined

Developmental states are those whose governing elites adopt and implement a realistic strategy of durable national development; usually because they have no other choice. The strategy rests on a diagnostic of the causes of under-development, the constraints to development and the deployment of the appropriate interventions based on available resources.

Oil-rich developmental states, not dependent on their population for endogenous production, invest in socio-economic upgrading as a hedge against political instability and long-term resource depletion. Non-oil developmental states must rely on their population, investing in socio-economic upgrading as the condition for durable development. Democracy is not an initial condition for development. But in non-oil countries it is a requirement for its durability.

The developmental state is a transition stage from low to higher performance. Developmental states are all deeply integrated into the global economy, and deeply interdependent with it. Endogenous modern developmental states do not exist.

Section 2: South Africa’s development problem

The failure of development strategy

Trajectory to failure

The socio-economic consequences of the pandemic have been brutal on South Africa. Lockdown is in its fifth month and will likely continue in some form into 2021. A sharp lockdown would have produced a short-lived recession. But with cases rising, the country is well past that point. At best, recovery will be slow. At worst, the country has entered a long-lasting and possibly self-perpetuating recession.

South Africa entered the pandemic highly vulnerable, weakened by a ‘lost decade’ of abusive governance and poor growth. It was in a steep decline, which we commented on in a Bloomberg article of April 2019 where we stated that “the likelihood of arresting the decline is limited by the unsustainable structure of South Africa’s economy, in which economic power is largely held by an elite that wields little political influence, a product of its apartheid history and its status as one of the world’s most unequal societies. The ability of politicians to make the unpopular decisions needed to boost growth is hampered by this imbalance.

Our pre-pandemic model forecasted that South Africa would fall into lower-middle income and very high fragility in the early-2030s. The pandemic has sped the clock up.

Democratic South Africa’s development challenge

The post-apartheid transition suddenly democratised South Africa, averting impending state failure. Its economy was comparatively sophisticated. But society had been structured on the exclusion and exploitation of the black majority, its middle-class prospects suppressed. Black labour was kept from competing with white labour. High unemployment, poverty and inequality – the infamous ‘triple challenge’ – were the resultants.

South Africa’s mineral resources had been the pillar of industrialisation. The economy was concentrated around segregated urban centres. Half of the population had been kept rural, without adequate socio-economic infrastructure. An exclusive first world co-existed with a vast third world.

Pressure on the first democratic government was enormous. But options were limited. The economy was concentrated and inefficient. Growth was low and volatile. Years of turmoil had cut investment. Government revenues had collapsed, expenditures increased. Resolving the country’s dichotomies represented the overarching priority. The ANC initially aimed for nationalisation, state monopolies and a universal welfare state. But goals collided with the depth of recession, the collapse of the USSR and the terms of the political settlement.

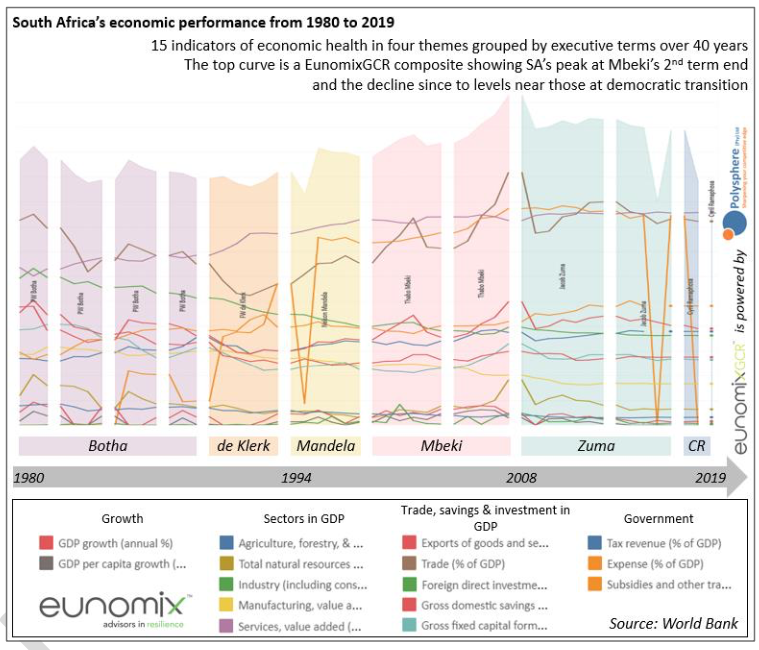

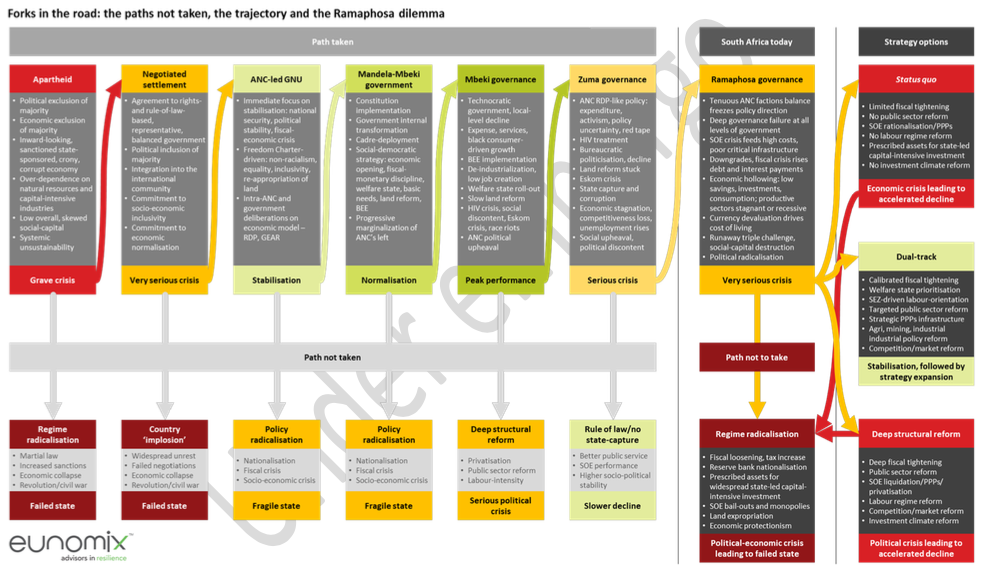

The ANC resolved to adopt a social-democratic approach, the economy to be opened, racially-skewed ownership to progressively shift through targeted intervention, a welfare state to redress deep inequity and care for basic needs, government to apply fiscal prudence. The initial shock to a self-imposed structural adjustment lasted until about 2000, after which growth picked up, and unemployment, poverty and inequality started decreasing. By 2005-06 the economy had greatly improved. For the first time in decades South Africa’s growth overtook world growth.

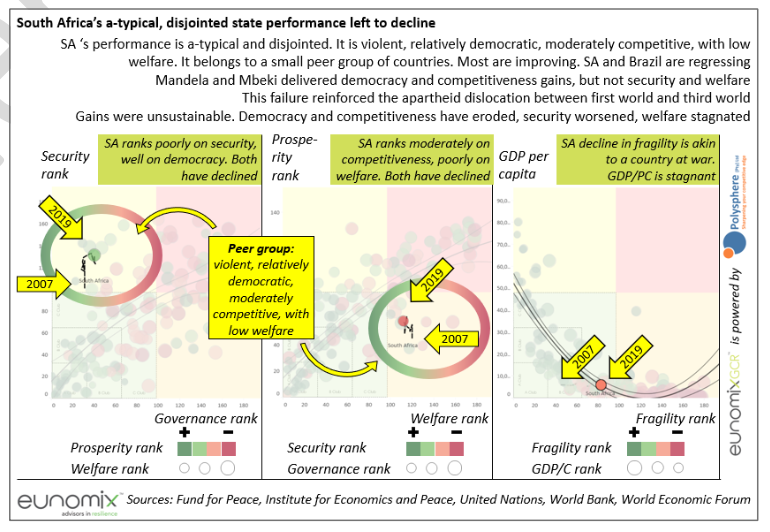

This was not to last. State performance peaked in 2006-07, after which decline set. It ranked 29th in governance, 44th in prosperity, 101st in security, 120th in welfare, and 37th in fragility. GDP growth reached 5.5% against world growth of 4% in 2006 – compared with 4% to 4.5% in 2000, and 0% to 3% in 1990.

The aborted developmental state and turn toward state failure

Creating a developmental state has been a central ANC ambition. But divergences over its meaning have divided the party. A change of direction in 2008-09 sought to bring about government-led socio-economic transformation – statism. The global recession offered timely justification for this, with calls for the nationalisation of key industries.

But the statist turn swiftly tripped over poor design, weak implementation capacity, mounting fiscal waste and fast-pace socio-economic reversal. Grand corruption took root. In an astounding act of economic sabotage, a party safely anchored in power erased in less than a decade of precious progress. The ANC aborted the developmental state.

The fall was swift. By 2018-19 the gains had been lost. South Africa now ranked 40th in governance – 11 places lost; 67th in prosperity – 23 places; 127th in security – 26 places; 112th in welfare – 8 places gained; and 94th in fragility. The loss of a staggering 57 rank places in fragility has been surpassed only by countries facing military conflict or internal collapse – Mali, Syria, Venezuela, Yemen. This number alone underlines the gravity of decline, the extent of the failure of the developmental state project, and the threat to the country’s stability.

Shifting state performance peers

Comparison with countries sharing similar rankings in state performance in our model provides key insight into South Africa’s performance, the scale of decline, and its most probable causes.

The peer group is made of countries that have been co-located along the state performance spectrum of security, governance, prosperity and welfare between 2006-07 and 2018-19. This group is composed of Brazil, Colombia, India, Jamaica, Mexico, the Philippines and Thailand.

They all have ranked poorly in security, governance and human development but relatively well in democracy – bar Thailand’s decline. They have ranked relatively well to poorly in prosperity, where significant shifts have occurred.

In 2006-07 South Africa and India were closest peers in GPD growth and competitiveness rankings, respectively 3rd and 1st in growth, and 2nd and 3rd in competitiveness. Thailand ranked 1st in competitiveness and Colombia 2nd in growth. South Africa lagged slightly in GDP per capita growth, ranking a close 6th to the Philippines.

In 2018-19 South Africa was the worst growth performer, its closest peers then Brazil, Jamaica and Mexico. India and the Philippines’s growth rates having remained over 6%, they joined the world’s top 30. In 2009-17 India’s growth averaged 7% per year to South Africa’s 1.5%.

GDP per capita declined by 3% between 2014 and 2019, the country ranking a low 135th. India and the Philippines’s GDP per capita expanded 25% in 2014-19. Together with Thailand they gained in competitiveness rankings, while South Africa, Brazil and Jamaica slid markedly after 2011, passing South Africa in 2012-13. They grew 40% faster in 2000-08 and 60% in 2009-17.

South Africa’s counter-performance is repeated across key socio-economic indicators. It has ranked 1st on per capita education and health expenditure, and 2nd to Mexico on the share of social transfers as a share of government expenditure – averaging 61% in 2010-2017, to the Philippines 25%,

India’s 40%, the world’s 42% and the OECD’s 55%. Yet, its welfare performance is stagnant. It ranks last in unemployment, poverty and inequality – among the world’s worst in unemployment and inequality. It ranks 3rd lowest in industry and manufacturing in GDP – the worst decliner. It ranks 3rd lowest exporter of goods and services – the worst decliner. It has the 2nd lowest savings and fixed investment, the lowest FDI and the highest consumption rates.

Natural resources, labour and growth

Our model holds that durable development must rest for its initiation either on vast oil resources sustainably deployed or labour resources – both requiring foreign investment and markets.

The resource rents of Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and South Africa averaged 4%f GDP in 2000-17, and around 7% in 2004-14. South Africa’s peaked at 13% in 2008, and over 7% during the cycle – the highest. Rents in oil-rich countries averaged 35% during the super-cycle, and 16% in mineral-rich countries. South Africa is at the low end of the resource wealth spectrum.

The lower the GDP growth/resource rents ratio the more resource-dependent growth is. Conflict-affected countries averaged 0.2 for 2000-17; oil-rich countries, 0.25; mineral-rich countries, 0.4; and least-developed countries 0.45. The OECD countries is 2.5. But manufacturing countries – 20% of GDP or more – have averaged over 6.

The combined ratio for Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and South Africa was 0.5; well below that of India, the Philippines and Thailand, with a ratio of 3. In the peer group, growth and resource rents have been mutually exclusive: growth of 2.5% to rents of 5. 1% for the first group; growth of 5.5% and rents of 2.5% for the second.

South Africa’s resource rents have not driven growth. They boosted it during a super-cycle which coincided with relatively progressive policy and governance. Commodity prices recovered after 2011 but growth continued to wane. Despite this, government introduced uncertainty in the mining sector, allowing a nationalisation debate to last for years and imposing arbitrary policy changes. The mining sector’s contribution to growth diminished.

No effort was made to increase labour mobilisation. Participation has been the world’s lowest since 2008 – 40% in South Africa against and declining continuously to 83% for the world. Thailand is 2nd in the peer group at 56%. Less than a quarter of South Africa’s population is employed, at an average of 22.5% for 2008-19, putting the country in 152nd position. A mere 10 million South Africans work out 58 million people.

This results in a relatively high GDP per person employed compared to peers, the country ranking 2nd in the group, 77th in the world for 2014-18. India is 112th, the Philippines 116th and Thailand 96th. However, this measure of labour productivity has been continuously declining – South Africa slipping from 65th to 82nd in 2000-18; 50% higher than the world’s in 2000, and now slightly lower.

These conditions should drive labour costs down as supply is vastly superior to demand. The opposite has occurred. South Africa’s wage bill in GDP is the 3rd highest among peers – lower only to Brazil and Colombia’s. It is much higher than those of India, Thailand and the Philippines – more than twice the latter. Between 2008 and 2019 the bill increased by 10% to 54% of GDP. Conversely, those of India and the Philippines reduced by 20%, and by 5% in Thailand. South Africa’s wage bill is now on par with those of Hong Kong, Japan and South Korea – advanced economies that have very high productivity, very high per capita income, are highly competitive and low levels of poverty and inequality.

Economic hollowing and the failed expenditure lever

Common explanations for the decline have been the global recession of 2008-10, which accounts for the sudden reversal in growth, and the Zuma presidency, which accounts for failed recovery thereafter. But this is as incomplete an explanation as is attributing the growth of the 2000s to Mbeki’s presidency. The apposition of the Zuma-Mbeki eras ignores fundamental continuities. Mbeki’s presidency undermined state capacity through cadre deployment, misdirected infrastructure investment – producing the Eskom debacle as one of its most dire consequences, and limited growth through sub-optimal policies. An extended Mbeki presidency would have likely produced only moderately higher growth than Zuma’s did.

Mandela and Mbeki understood that fiscal discipline improved economic sovereignty. They leveraged relatively good economic infrastructure and a capable private sector to take advantage of a new world order and tremendous goodwill, attracting investment and opening trade. The economy was opened-up and adapted. The commodity super-cycle aided growth. But the narrow, exclusive resource and capital-intensive structure was reproduced, and its continuation remained the development strategy.

Service delivery protests, the ANC leadership change of 2007, load-shedding and the 2008 xenophobic attacks underlined the consequences of low growth. Zuma inherited a relatively sound economy only to face a global recession. Indifferent to policy detail, opposed to fiscal prudence, he seized the moment to expand statism – supported by an ANC’s left hungering for a state-centrism it believed Mandela and Mbeki had abandoned. The fragile foundations of growth were sapped by worsened policy, fiscal profligacy, institutional capture and grand corruption.

Buttressed by a left remorseful of its support to Zuma on one side and nationalists on the other, Ramaphosa has sought a course in-between. Adopting superficial pro-growth discourse, he has maintained the strategy and thus accelerated social, economic and political adversity.

The long-predicted call to the multilateral financial institutions for support comes too late, the product of mismanagement by those who swore never to surrender to the ‘Washington consensus’ institutions. The pandemic is the last nail in the coffin of a strategic fiasco.

The economy is unsustainably narrow and shallow. It rests on a small and declining working population burdened by very high debt and taxes. The primary and secondary sectors have bent under poor policy, bad governance, declining competitiveness and low growth.

The service sector meagrely compensated until around 2015, bubbles in real estate and retail having since burst. Investment has withered, imports grown, foreign debt increased, undermining the balance of payments. Currency devaluation has hastened as a result. A war-cry of the labour unions who demanded competitive devaluation to maintain an advanced economy labour regime, devaluation has produced no ‘export-supply response’. To the contrary, imports have increased to 25% of GDP.

South Africa’s economy has been rapidly hollowing out, the sources of growth exhausted, productivity falling irrepressibly. Unemployment, poverty and inequality are at record levels.

Agriculture and mining, pillars of the economy, have been relentlessly targeted for transformation, handicapped by unceasing policy change and uncertainty – not to mention the Eskom crisis. In doing so, the ANC has sapped the foundation of its mineral-energy complex development focus. It has reduced the growth, revenues and unemployment contributions of these sectors, turning a vital source of competitiveness away. The country now ranks low in key metrics of investment and investor confidence in these sectors.

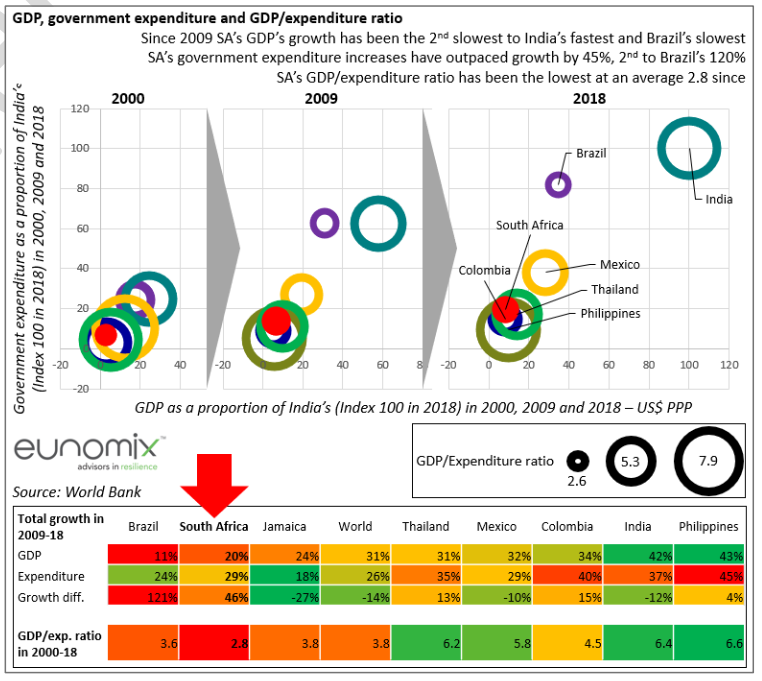

High government expenditure has sought to compensate for declining performance, to fast decreasing efficacy. Expenditure in GDP in the highest in the group, averaging 34% of GDP for 2010-17 and rising – from 27% in 2000 to 35% in 2017. India’s average for 2010-17 is 15.5%, the Philippines 14%, the world 27%.

South Africa has had the lowest ratio of unit of GDP per unit of expenditure among peers: half that of India and the Philippines. Moreover, the ratio has been falling 10% per decade. With each new Rand of expenditure there is less GDP than with the previous, underling the decreasing returns of the expenditure multiplier. Public expenditure cannot make-up for the gap in savings, investment and economic activity. The expenditure multiplier has failed.

A fundamental error of development strategy

South Africa’s astonishing economic decline is the inescapable outcome of an economic structure not matched to the country’s developmental requirement. Natural resources are insufficient to fuel growth. Capital-intensity is not aligned with comparative advantage. The workforce is largely kept out of production. Growth is thus mechanically limited to levels unable to alleviate unemployment, poverty and inequality. At the best of times the economy fails to make durable progress – as was the case in the 2000s, and at the worst of times it grinds into lasting recession and greater fragility.

This economic structure and its hollowing out are both the consequence of a fundamental error of development strategy on the part of the ANC.

Strategy should have been entirely focused on shifting the structure of the economy through sustained diversification aligned with comparative advantage. It should have consolidated its primary sectors as generators of rents to be reinvested in employment-creating diversification. Instead, it has systematically amplified a self-created Malthusian trap by hobbling the very sectors on which the economy has depended the most while undermining diversification by directing scare resources toward ill-fated capital-intensive industrialisation, all the while resisting widespread inclusion of unskilled labour in production.

Political-economy trap

Colonisation and apartheid created a system whose survival depended on the violent exclusion of the majority. The apartheid elite was incentivised to resist large scale labour mobilisation because doing so would have shifted the political-economy balance toward the majority. The regime feared a black middle-class as much as it did a general uprising.

Democratisation ended formal political exclusion. But through its failure to reverse economic exclusion, the ANC replicated a central attribute of apartheid. While the latter suppressed the majority, democracy has subsidised it. But both locked it out of the productive economy, and in doing so precluded durable development. Rejection of labour-intensive-export-orientation as a cornerstone of development has been the foundational mistake of democratic South Africa. In doing so, the ANC has crystallised the poisonous divorce apartheid established between economy and politics. This divorce has incentivised the political elite against adopting a sustainable development strategy.

Four factors have contributed to this.

First is the belief that unemployment, poverty and inequality remain products of the confiscation and ongoing exploitation of land, minerals and labour by ‘white monopoly capitalism’. Labour-intensive-export-orientation, this belief holds, would only reinforce exploitation, alienation, and lock the country into the ‘race to the bottom’.

The conflation between apartheid’s racist corporatist capitalism and labour-intensive-export-orientation is absolute.

The second is the belief that natural resources – land and minerals – are abundant enough to underwrite durable development without labour mobilisation. The ‘mineral-energy complex’ and beneficiation have been key foci of an industrial policy that has funded extensive infrastructure, incentives and projects.

The results have been unimpressive and costly. In parallel, mineral policy has deeply damaged the mining sector, and energy policy electricity generation. Land reform, an absolute necessity, has ground to a halt. The conflation between natural resources and development is profound; absurd and destructive contradictions between key policies, as well as poor implementation and resource diversion through corruption notwithstanding.

Third is the ANC’s political dominance, which is not simply rooted in ideology but on its struggle and liberation credentials. These are the source of a tremendous organic connection between a sizeable majority and itself.

Twenty-five years into democracy the ANC still commands the loyalty of around 60% of South Africans. There is a profound and persistent disconnection between this unfailing loyalty and the level of disapproval of government performance.

The fourth factor is the vast system of patronage that comforts the ANC’s political dominance, particularly in rural South Africa where the party’s majority is overwhelming. ‘Cadre deployment’, social programmes, government procurement and widespread corruption have cushioned it from the political consequences of economic failure. Cronyism has entrenched vested interests militate against true economic inclusivity in favour of self-selected enrichment.

These factors are mutually reinforcing. Continuous economic contraction increases the political influence of the poor and of the crony capitalists. The middle-class and the private sector diminish in economic weight and therefore in political influence.

South Africa has thus been afflicted with a strange case of the resource-curse, natural resources being insufficient to underwrite the economy but enough to maintain the elite project.

Elite power, pandemic and economic failure

Strategy change will occur only when the ruling elite is incentivised to change course or has been replaced. The pandemic and its effects do threaten the political status quo, presenting risks to the ANC and affecting the tense balance of power between factions. The loss of 1 million jobs or more, the closure of thousands of businesses, a recession unlike any before are profound economic blows. Government revenues have been badly affected, necessitating fiscal tightening and debt raising to record levels. Lending from the IMF, a political taboo, is now a fact. These factors strengthen the position of the orthodox faction of the ANC in the long-running battle between it and the left and populist wings of the party.

But these factors and their implications must not be overstated. The orthodox faction is a minority, and its hold on the Reserve Bank and the Treasury tenuous. Their mandate is to limit fiscal damage, not reform the economy. The IMF loan equivalates a mere 6% of the 2020 budget, 4% of the national debt, and 1% of GDP in real terms. Though debt is slated to reach 100% of GDP, this is a much a symbolic as it is an economic watershed, and does not mechanically bring reform. Contrary to the hopes of many, and the fears of more, the multilateral financial institutions do not have the power to change an economic strategy. At best they stabilise a crisis, at worst they enable the status quo.

The pandemic also brings opportunity to the party. It has strengthened the government’s hand in the economy, since March ruling through administrative fiat, without consultation and with scant justification for its drastic, often contradictory decisions.

Political and legal challenges have been minimal, and Ramaphosa’s handling of the crisis is widely praised. The microeconomic policy has long been the preserve of the leftist faction. Through the pandemic, this has turned into micromanagement of economic activity reminiscent of collectivism. This reinforces power. It also provides ample resources for influence and enrichment.

More fundamentally, the sudden acceleration of economic hollowing primarily impacts a private sector-employed urban middle-class the ANC has, in the main, politically written-off. Business organisations have limited influence. These factors do not meaningfully threaten the ANC’s hold on core voters who are ever more dependent on the welfare system for its livelihood. Brazen pandemic-related corruption reveals a confidence that belies the notion that the party feels threatened.

The crisis has for now consolidated the longstanding balance of power between an orthodox faction traditionally in control of the fiscus and a leftist-nationalist faction traditionally in control of economic activity. Reform is disabled, and as has been the case for over a decade, the fiscus manages decline.

Rather than encouraging reform, crisis and discontent may accelerate the already powerful drive for increased economic populism. It already has a solid base within and outside the ANC. As the balance of political-economic influence shifts further to the rural and urban poor, the political appeal of economic radicalisation will be a temptation difficult to resist.

Quo vadis, South Africa?

One of the key functions of EunomixGCR is forecasting and scenario-planning for strategy and country risk management. Our first forecast was issued in 2016. It calculated that by 2021 South Africa would have declined to 42nd in governance and 65th in prosperity.

The country ranked 40th in governance – marginally better than we forecasted – and 67th in prosperity in 2018-2019 – measurably worse than our forecast.

Our forecast to 2030 excludes the effects of the pandemic. Using two different baselines, it sets the ranking range as: 40th-65th in governance, 90th-115th in prosperity, 150th-170th in security, 95th-120th in welfare, and 135th-180th in fragility.

Excluding the effect of the pandemic, we are 75% confident that South Africa will rank close to 160th in security, 50th in governance, 100th in prosperity, 110th in welfare, and 160th in fragility by 2030.

Countries currently ranking around these marks include: security: the DRC, Israel, Nigeria, Pakistan, Russia, Ukraine and Venezuela; governance: Argentina, Bulgaria, Ghana, Panama, Poland, Slovakia, and Trinidad; prosperity: Argentina, Bangladesh, Bosnia, Cote d’Ivoire, Dominican Republic, Laos and Nicaragua; welfare: Bolivia, Egypt, Gabon, Indonesia, Moldova, Paraguay and Vietnam; and, Fragility: Burundi, Cote d’Ivoire, Kenya, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan and Zimbabwe.

From a peer group perspective, there currently (2018-19) are no countries where South Africa is forecasted to be in 2030, underlining the a-typicality of its trajectory. However, current countries in performance clusters security-governance and prosperity-welfare include Lebanon, Nigeria, Turkey and Ukraine for the first; Gabon, Nicaragua, Mongolia and Tunisia for the second.

Bar a meaningful change of trajectory, South Africa will be a failed state by 2030.

Section 3: South Africa’s narrow path to sustainable development

It’s all politics

Our diagnosis of South Africa is derived from our model’s identification of the conditions for state performance and durable development. We have located the country along the state performance spectrum and identified its peers for a deeper, comparative investigation. This has produced a rich perspective on South Africa’s performance, trajectory and likely direction. Our forecast anticipates state failure within a decade or so. Our analysis has provided a powerful account of the causes of the country’s decline.

Simply stated, it’s all politics; economy be damned. Should additional evidence be required to seal that pronouncement, the end of Mbeki’s presidency offers it. At peak performance, the ANC ended the most successful policy in a generation, dissolved the team that designed and implemented it, and delivered unending crisis with political impunity.

In the medium to long-run, only the adoption of a labour-intensive-export-oriented strategy would open the path to more durable development, provided it is accompanied by social-capital enhancing investment. Through this, the country could turn it into a continental economic powerhouse, stabilising society in the intervening period. It has one of Sub-Saharan Africa’s largest labour forces.

It still ranks well in some industries, services and infrastructure. It has a comparatively sophisticated private sector able to invest in export-oriented manufacturing and services. It possesses a leading financial sector that can mobilise international and domestic capital. It has a small but competitive market for manufactured products. It has extensive international market access. Its time zone is aligned with Europe’s, in-between America’s and Asia’s. Its labour force is fluent in English and multilingual.

Politics obviously conspire against such a strategy. Simply advocating for its adoption on mere economic grounds is in patently self-contradictory. If politics is the cause of decline, politics must be its solution; technical solutions, no matter how sensible, be damned. Or worse, technical solutions be a diversionary tactic to hide inaction through motion, or, like the call for ‘prescribed assets’ to fund ‘developmentalism’ – likely another scheme for salvaging patronage, cronyism and corruption.

Current proposals for turnaround

The pandemic has fostered recovery blueprints by political parties, organised business and labour, and a variety of expert groups. The ANC has produced a document entitled ‘Reconstruction, Growth and Transformation’, and a coalition of business organisations called B4SA has released an ‘Accelerated Economic Recovery Strategy’.

The ANC proposal rests on a vast list of priorities structured in three thrusts: infrastructure investment and financial mobilisation, promotion of a wide set of sectors, and the building of “a capable, ethical and entrepreneurial developmental state”.

Capital-intensive manufacturing is to be targeted, from textile, consumer goods and appliances, transport equipment, engineering products to mineral beneficiation. Labour-intensive activities must also be targeted through ‘low end’ manufacturing and vast social and environmental services. The proposal finds in the pandemic justification and opportunity “to kick-start a massive programme of localisation.”

With roots in the decades-old Reconstruction and Development Plan and the decade-old National Development Plan, the document underlines the opportunity for the party to use its ‘hegemony’ to decisively drive recovery.

It affirms that the pandemic “has legitimized a greater and more active role of the state in guiding the economy.

Thin on self-introspection, economic analysis and supporting evidence, the document exposes the ANC’s inability, twenty-five years in power, to take responsibility for its own failings. It ignores the key constraints to growth: from the rigid labour market and adversarial industrial relations environment, to the high cost of doing business and policy incoherence and regulatory inefficiency. It repeats the recycled hope that this crisis – just like the ones of 1993, 2001 and 2009 – represents the opportunity for state-driven, capital-intensive, inward-looking development.

The document reproduces the ANC’ failed understanding that the developmental state is a descriptive concept. It treats it instead at once as a condition-precedent to development through a vast capacity-building programme – a sort of ‘project within the project’ – and as the statism in action.

Not only is this patently illogical, but all evidence shows that the continuous decline in government capacity and ‘state capture’ are the outcome of ANC ‘hegemony’.

The B4SA document represents a significantly more pragmatic proposal for rapid recovery and long-term “inclusive economic growth.”xvi Its aims are “restoring confidence, attracting investment, and implementing projects leading to near-term employment gains.”

Presented as a basis for intensive engagement toward a development compact – a concept also espoused by the ANC document, ‘hegemony’ and statism notwithstanding – it proposes a series of 12 initiatives spanning sectors and seeking to resolve cross-sectoral and economy-wide constraints. As is the case with the ANC document, it emphasises infrastructure as central condition and opportunity for growth.

Unlike the ANC document, the B4SA document focuses on the criticality of policy, investment climate and investment and growth enablers. It also identifies 12 “key policy focus areas”: corruption, the business environment, labour legislation, state-owned enterprises reform, education, policy incoherence, etc. The document estimates the cost of its initiatives at about R3.5 billion, which cannot be met by the domestic economy and requires accessing international capital for debt and equity.

The B4SA document restates prescripts long advocated by business organisations. Many are correct. The infrastructure proposal is overstated. South Africa is comparatively well-endowed in economic infrastructure, but suffers from its high cost and inefficient administration. The set of sectoral priorities is too wide.

But the most serious assumption is that government and the public sector have the technical capacity to play their parts, and that the ANC has the political will. As regards the first, placing so much emphasis on rapid, coordinated action by a government that struggles to keep the electricity grid from collapsing carries the risk of turning the proposed strategy away from rapid recovery and toward the developmental state-building tautology.

The politics of strategy reform in late-late developers

South Africa is not alone in its political-economy predicament. Many countries over the past thirty years or so, particularly post-colonial ones, adopted politically unpalatable strategies because their situations demanded it. We described the nature of these countries’ ‘meta-strategies’ in the essay’s first section, but not why and how they addressed the political-economy blockages that stood in the path of strategy adoption and implementation.

In rare cases was this due to exceptional leaders. Rather, through political pragmatism, political and business elites searched and found compromise spaces, adapting through experimentation, failure and course-correction. Most eschewed the false opposite status quo and economy-wide reform. Most sought to resolve the political-economy gap that pitted government against business. Such were the trajectories of China, Korea, Malaysia and many others; post-colonial societies marred by dislocation between economic elites and political ones, ethnic division, vast poverty, insufficient social and financial capital, and facing uncertain futures.

No different was the situation of tiny Mauritius, whose newfound success in the late 1980s-early 1990s the World Bank claimed as its own as a model of a late-late developer’s adoption of structural adjustment. But the institution failed – or did not want to – see the selectivity of reform, the accommodation of vested interests, the preservation of trade and investment protection afforded to select sectors and businesses provided they did not oppose the government or invested in the labour-intensive-export-oriented program.

Most successful late-late developers adopted dual-track economic development, one foot in statism and the other in selective market-reform, one foot in protectionism and the other in liberalisation. Deng-Xiaoping famously called this prudent approach “crossing the river feeling for stones.” In none of these cases did export-oriented-labour-intensity replace established strategies – whether collectivist, import-substitutive, or capital-intensive-export-driven.

Restructuring rather than reform is the shared attribute, a progressive process set over a decade or more, that gradually gains acceptance and support through the polity as labour-intensive-export-led growth makes its case through employment creation and growth acceleration. Eventually, the tracks merge into diversified economies with low levels of unemployment, more sustainable fiscal resources and high levels of social capital providing improved socioeconomic resilience.

Much debate on the merits of the dual-track approach has taken place since the 1980s, and continues today. For some, the strategy cost precious time, acting as ‘reform-delay’ in countries that would have otherwise grown faster. For others, it alleviated the deep political-economy impediments that had previously limited growth and undermined development. The dual-track strategy’s initial low growth is an attribute of its purpose – not a mark of failure.

While shielding inefficient sectors might have cost growth, do so while selectively opening-up also limited the socio-economic, and therefore political, cost of reform and liberalisation. Advocates of the dual-track strategy point to the devastating effects of structural adjustment across Sub-Saharan Africa.

But the strategy has its limitations. In very fragile states its adoption is obstructed by the inherent political weakness of government and by the depletion of state capacity to design and implement it. SEZ programmes across Sub-Saharan Africa have seen a resurgence in the past decade. Few have been successful, hobbled by these factors, and by strong opposition against any reform by vested interests – bureaucratic ones included.m Dual-track requires a modicum of capacity and political will. In a declining state there is a time-limit to its adoption, beyond which it is too late, and state failure becomes inevitable.

Adopting a dual-track, special economic zone-centric strategy

Considering the formidable political, technocratic and economic obstacles against reform, and given the urgency of employment-generating growth, the dual-track strategy appears to be one of the few options available to South Africa. The strategy represents a pragmatic compromise between contesting elites designed to prioritise employment generation, maintain necessary social expenditure and target infrastructure investment and select reform. In the short to medium-term if falls short of elite expectations, whether on the left or the right, in government, business or civil society.

While it cannot immediately create fast growth, it can arrest decline and deliver accelerating growth in the medium-term. In the longer-term, it requires significant investment of social capital upgrading.

The seed of a dual-track strategy for South Africa already exists, hiding in plain sight in the special economic zone program. Barely mentioned in the ANC document, it does not seem to feature in the B4SA proposal.

Adopting an SEZ-centric dual-track strategy makes economic sense where the ANC proposal does not, and political sense where the B4SA proposal fails to. The strategy could rapidly attract investment, generate employment, and thus lower the pressure on the economy. It would target labour-absorbing industries like agro-processing, light-manufacturing, and customer-centric services on a large scale. Consideration should be given to tourism, renewable energy and data centres. Mineral exploration and development, long-neglected and vital to the future of mining, could be given SEZ status.

In parallel, instead of strict fiscal tightening, government would increase support to the vulnerable, the unemployed, and the sectors most affected by the pandemic. It would maintain the welfare state, current levels of public sector employment, and develop only the most promising infrastructure projects and sectoral initiatives in cooperation with the private sector. International financial institutions would need to provide fiscal support for the country endorsing the dual-track strategy. Reform, fiscally and technically infeasible, politically unacceptable, would be eschewed in favour of restructuring – crossing the river feeling for stones.

This pragmatic method would demand the urgent and profound restructuring of the SEZ programme. Its economic impact has been low because of its focus on capital-intensive industries, high infrastructure and subsidies costs, and onerous governance structure. Ironically, the South African SEZ programme has reproduced many of the strategic failures and attributes of the domestic economy, nullifying its effect and contradicting its purpose.

This would cost little resources and time, priorities being the simplification of the SEZ Law and regulations and the elimination of unnecessary red-tape. The current SEZ tax and customs regime are broadly adequate, as long as their administration is significantly improved. The planned one-stop-shop should give way to a single delegated SEZ licencing and permitting authority where SEZs are represented. Investment in the development, management and promotion of SEZs would be meaningfully opened to the private sector – thus lifting a burden on government resources and generating scarce private sector investment. The SEZ Board would introduce effective private sector representation and influence. Axiomatic to the strategy would be the streamlining of labour practices and the easing of black economic empowerment requirements in the SEZs.

In time, with the SEZ programme expanding, its socioeconomic contribution increasing, the dual-track strategy would lead to progressive economic restructuring. Government could then gradually decrease support to uncompetitive industries while improving support to those that are promising ones. The current practice of subsidising government-preferred sectors while disincentivising ill-favoured sectors would shift to a system of incentives and taxes. Fiscal and technocratic resources would prioritise the human development and social capital upgrading that are pivotal to a sustainable development strategy and key to avoiding the ‘race to the bottom’. Government would also prioritise critical infrastructure in a cost-to-consumer neutral way.

The ANC’ strategy is, ultimately, the product of a false dichotomy between state and market, government and private sector, endogenous and exogenous growth, capital-and labour-intensity; a dichotomy born of apartheid, resistance and crystalized by ideological puritanism and entrenched interests. The country should not choose between imagined opposites. It should adopt a dual-track approach that reconciles them. BM/DM

Claude Baissac is CEO of Eunomix, a geopolitical and country risk consultancy. Baissac has spent the past 25 years in the industry advising governments and companies on how to assess country risk, in the process, developing a data-centric model to enhance this evolving discipline.

![]()