Children’s Book Combines the Wisdom of the Talmud with the Ancient Poetry of Rumi

It’s not every day that the sages of the Talmud and the ancient Persian poet, Rumi, cross paths. That’s why I was so thrilled to read “The Adventures of Rumi and Baruch Bear,” a vividly charming new children’s book by Yehuda Rothstein.

It’s also not every day that the main character of a Jewish children’s book is an Iranian Jewish girl, especially when so many of these books depict Ashkenazi characters, Ashkenazi villages, and disproportionate references to, what else? Matzo balls.

The book begins by introducing a young girl named Rumi as she gazes out of a window in her room in Tehran. Yes, Jews live all over the world, even in Iran, and in recognizing this important fact, Rothstein demonstrates his transparent passion to shine a light on the beautiful diversity of global Jewry.

On Rumi’s wall is a drawing of the tombs of Esther and Mordechai in the northern Iranian city of Hamadan. On her desk: computer screen, a keyboard, and a book titled “C++ Computer Programming.” As my eyes caught sight of the dark-haired Rumi (accompanied by her imaginary companion, Baruch Bear)—who seems to own her Jewish identity, Iranian roots, and yes, the study of computer science—I realized how much I already like this unique little girl.

The book, which is meant for children seven years and older, follows Rumi as she tries to “understand the questions of her heart.” She is guided by her loving mother, grandparents, and her great-grandfather, as well as teachers and friends. “One day,” the reader learns at the beginning of the story, “Iran was no longer safe for Rumi and her family.” These are exactly the same words I use to describe my family’s escape from Iran when I tell the story to my young children.

Rumi’s family resettles in New York and she admits that she’s afraid to attend school because of a stutter, worrying that no one will understand her. In highlighting Rumi’s stutter, Rothstein again compassionately breaks out of the mold of most Jewish “kid lit” (children’s literature)—especially picture books—by presenting a little girl’s struggles in direct parallel with her fears and potential.

“Moses himself was a stutterer and accomplished great things after overcoming many different challenges,” Rothstein told the Journal. “I wanted Rumi to stutter because I wanted her to be different beyond just her Persian ethnicity in an Ashkenazi environment; a stutter is really a metaphor for what we all go through in life. We all try to strive in a way that moves forward our life agenda, but we often take missteps. We make mistakes, we say the wrong things—we stutter. Accepting ourselves, but at the same time, moving forward and growing, is part of life.”

Rothstein succeeds in creating an endearing compromise between telling a simple story about a girl who wishes to find her place in the world and rendering Talmudic wisdom (and the delicious poetry of Rumi) digestible for children. In fact, “The Adventures of Rumi and Baruch Bear” offers such a treasure trove of wisdom that adult readers will be hard-pressed to ignore its sage advice. When Rumi’s mother speaks harshly to her for hesitating to attend school, her grandfather intervenes, echoing the poet Rumi by advising, “Raise your words, not your voice. It is rain that grows flowers, not thunder.”

This is precisely how Rothstein manages to offer such complex poetic wisdom: eloquent counsel is offered by characters as a response to Rumi’s struggles to make friends and forge her own path. Even Baruch Bear espouses wisdom, such as when he responds to Rumi’s question about whether she will grow up to have a lot of friends: “All I can say is this: Who is wise? She who learns from others,” say Baruch Bear, quoting Pirkei Avot 4:1 (“Ethics of our Fathers”), while adding, “But do not blindly follow the stories of others that came before you” (wisdom from the poet, Rumi).

It’s time for a children’s picture book as vivid and inclusive as “The Adventures of Rumi and Baruch Bear.” I wish I had had the poet Rumi’s words, decades ago after I first came to the United States, to soothe me each time I felt anxiety about attending my new American school. I was especially drawn to a conversation in the book in which Rumi’s mother reassures her, “Ever since the dawn of your life, friendship heard your name and it has been running through the courtyard trying to catch you. You must let it.”

How’s that for soothing? Yes, if only “The Adventures of Rumi and Baruch Bear” had existed when I was a child. While I deeply yearned for friends, sometimes I felt as though the only person who ever tried to catch me was Ayatollah Khomeini (and Saddam Hussein during the Iran-Iraq War).

“The Adventures of Rumi and Baruch Bear” is Rothstein’s first children’s book. A New York-based transactional real estate and construction law attorney, he previously was a Fulbright visiting scholar at the University of Toronto Faculty of Law, where he lectured on Comparative Islamic and Jewish Law. Rothstein specializes in Muslim-Jewish relations and in 2017 was appointed a board member of the New York Muslim-Jewish Advisory Council (he also served as a Broome Fellow of Muslim-Jewish Relations at the American Sephardic Federation in New York City). He is currently the Editor-in-Chief of the Jewish-Muslim Sourcebook Project, which works with the Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement at the University of Southern California. Rothstein is also a World Jewish Congress delegate and a real estate investor.

Rothstein grew up in Monsey, New York, home to one of the largest Orthodox Jewish communities in the country, and studied Talmud and Jewish studies for more than six hours a day at an all-boys yeshiva.

“In Monsey, the average family had five or six kids. And so everyone, including the men, learned a lot about children, how to nurture them, and to value them and appreciate family more generally,” he said. “It’s a very different world than most readers probably know.”

But growing up in Monsey, Rothstein seldom found depictions of Jews that closely mirrored him and his family. “I come from a diverse multicultural and multiracial Jewish background, and as a child, I didn’t see depictions of what we call Jews of Color or Mizrahi Jews in textbooks or learn about the rich history and diversity of our people,” he said. In elementary school, Rothstein saw handouts featuring cartoon pictures of Moses, Aaron, and other Jews in the Torah. “They all looked Ashkenazi and Haredi,” he recalled. “Moses and all of the Children of Israel who followed him into the desert were wearing shtreimels (fur hats worn by Hasidic men) and long coats.”

Rothstein remembers being taught that even Jewish scholars were only Ashkenazi. “Not only were all the biblical characters depicted as Ashkenazi, but all the heroes, all the great rabbis of history, were, too,” he said. “I remember my teachers saying to me that all the great rabbinical scholars or gedolim (great rabbis) of history were Ashkenazi Jews. I was told that there weren’t any great rabbinical figures in the Mizrahi world.”

But Rothstein believes that excluding Sephardic, Mizrahi, and others Jews of Color isn’t only a challenge in the Haredi world. “It isn’t only a problem relegated to the Orthodox world; it was true even in my secular Judaic Studies classes in university,” he said. “It occurs in Reform and Conservative circles I’ve traveled in, too. It’s a larger problem in American Jewry, and something that we need to repair in our culture. My book is a humble attempt to address this issue.”

Still, he doesn’t think of himself as “one kind of a Jew or another kind of Jew, or Ashkenazi Jew or Sephardic Jew. I’m just Jewish, and so I look at every single Jewish communal experience as part of my story.”

Still, he doesn’t think of himself as “one kind of a Jew or another kind of Jew, or Ashkenazi Jew or Sephardic Jew. I’m just Jewish, and so I look at every single Jewish communal experience as part of my story.”

Rothstein was especially influenced by his friendship with an elderly Iranian Jewish man named Shlomo Sakhai, who passed away in 2019 in New York. “He was a real hero and humble leader of Iranian Jewry, and one of the most generous but unassuming people I’ve ever met,” Rothstein recalled. “Shlomo was an orphan child in Isfahan, selling matches on the street corner as an eight-year-old boy. A deeply spiritual man who was focused on helping the community, he became one of the leaders of Iranian Jewry, a bridge-builder and peacemaker. He secretly gave charity to his neighbors, both Jewish and Muslim, and even adopted an orphan Muslim child that he raised as his own. When he died, Muslims in Tehran set up a mourning tent.”

Rothstein spent many Shabbat and holidays with Sakhai, where he learned the particulars of Persian culture: “I knew from my experiences with Shlomo that Rumi’s words and ideas are on the lips and heart of every literate Persian. But likewise, the words of Torah were also on his lips, and on the elders of the community, at all times. And so, I thought, it would be interesting to marry the wisdom of Rumi and the wisdom of the Talmud together, much in a way that they came together in someone like Shlomo.”

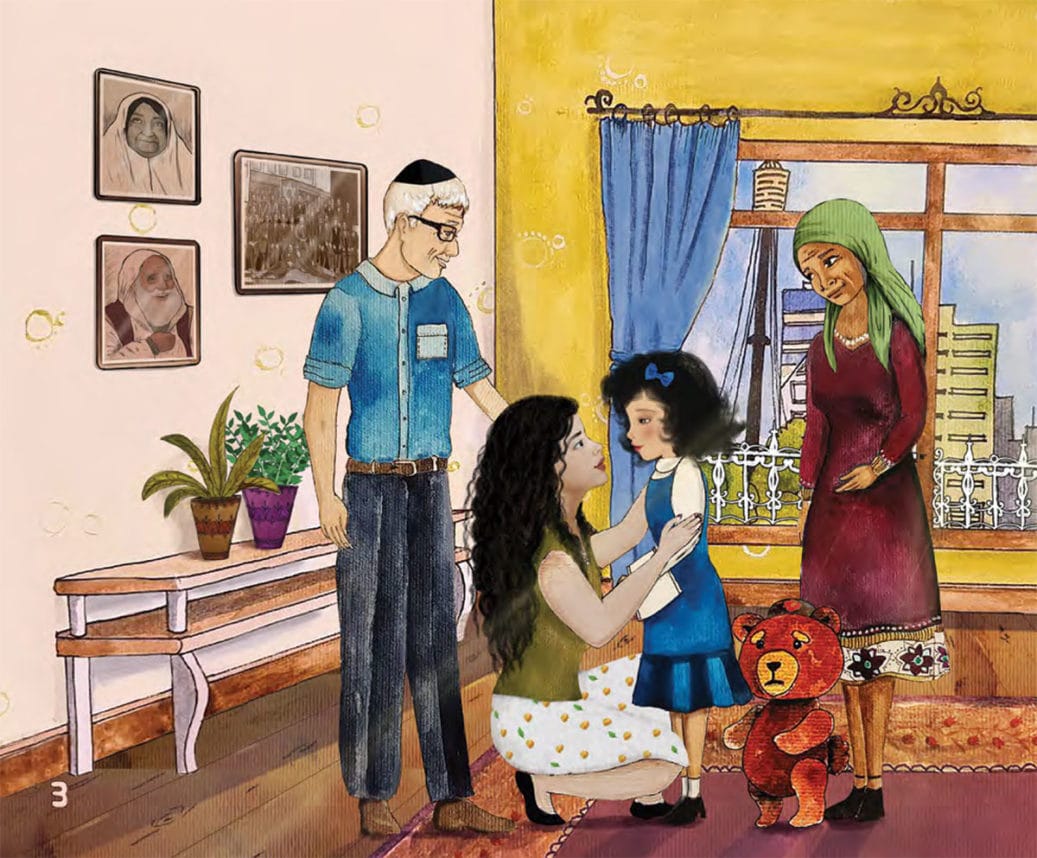

The illustrations by Nasim Jenabi, a non-Jewish Iranian immigrant who resides in Canada, are particularly striking. “I think the best part of this book is Nasim’s art,” Rothstein said. Jenabi demonstrates an instinct for drawing characters and scenes in ways that truly capture the richness of the Mizrahi Jewish experience: an artistic print on a little boy’s skullcap; a circa-1920s picture on a wall in Rumi’s house that shows fez-clad Iranian Jewish men gathered at a meeting of the Zionist Federation; Rumi and her family at the Shabbat dinner table, surrounded by heaping plates of gondi (an Iranian Shabbat specialty consisting of ground chicken, chickpea, and cardamom meatballs). There’s something almost mystical about Jenabi’s illustrations. Together with the text, this is a book I am deeply proud to show my own children.

“The Iranian Jewish story is really part of one of the first diaspora communities, and its contributions to world Jewry are immeasurable,” Rothstein said, adding, “How is it possible that there are so many Persian Jews in the United States and there is little to nothing about them in our textbooks and cultural centers? How is it that everybody knows about matzo balls, but not gondi balls as a delicacy on Shabbat?”

Rothstein also created a website where readers can download a free parent and teacher guidebook to facilitate discussion with children. “The Talmud says that each child is a clean, smooth piece of paper ready to be inscribed with all the potential of the world, as opposed to us adults who are likened to crinkled sheets of paper,” he said. “If we educate our children correctly, as children’s books have the potential to do, then they will adhere to those values when they are adults and we are gone.”

His commitment to ensuring that Jews around the world know and appreciate diverse Jewish customs is deeply inspiring: “We are taught that a Torah that is missing even a single letter isn’t kosher,” he said. “Our people belong to a single body. How can the left hand not learn about the right? If we don’t show the diversity of our people, then we are missing a part of ourselves.”

Tabby Refael is a Los Angeles-based writer, speaker and civic action activist. Follow her on Twitter @RefaelTabby.